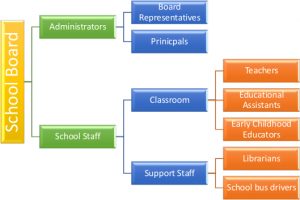

Figure 1. Proposed participants for study of understanding bullying prevention program functioning within school systems.

Summary

Trickett, E. J., & Espino, S. L. (2004). Collaboration and social inquiry: Multiple meanings of a construct and it’s role in creating useful and valid knowledge. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1/2), 14–69. http://doi.org/10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040146.32749.7d

- Often, Lewin is credited with the birth of the perspective as he felt that traditional approaches were not useful for addressing social problems. Explores the epistemological underpinnings of collaborative research are utilized by feminist scholars, community psychologists, and program evaluators. It is increasingly being used within the health sciences, by community health researchers, and for organizational development.

- The goal of collaboration within research is to make research more impactful through creating a more egalitarian relationship between the researcher and the researched. The approach acknowledges that both parties have expertise that is essential for effective problem solving.

- There is a strong emphasis from ecological and empowerment perspectives. Through engagement in the research, collaborators (potentially disadvantaged or marginalized) from the community are empowered and can take ownership of their knowledge, decisions, and lead the way to social change. However, it is essential to acknowledge and account for the complex sociopolitical context in which the problem being explored occurs.

- Collaboration, ideally occurs at all stages of research, from conceptualization to dissemination.

- Pragmatically, collaborative-participatory research is informed by those living within the context being investigated, therefore the research itself is more useful and knowledge can more readily be utilized. There is a shift in focus from the individual to the community as a larger entity.

- Ultimately, it attempts to bridge the gap between research and practice, acknowledging that to solve a problem, the unique context must be accounted for, as the research or intervention may not be sustainable once the research funding, the researchers, and other potential resources have left. Through collaborative participatory approaches, we can seek to develop research that is more sustainable, useful, and have more validity to our findings (due to the participants/collaborators providing their input on the analyses along the way).

Minkler, M. (2004). Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 31(6), 684–97. http://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104269566

- Ideally, community-based participatory research will begin with a call or need from the community itself. Often it has been questioned whether research coming from academia to the community can be community-based and collaborative. However, Minkler and others argue that part of collaboration is acknowledging the strengths of everyone participating in the research project. Therefore, the academic maybe the initiator, but they will still need to develop buy in from the community.

- If the researcher is lacking in expertise or connections within the community, it is recommended that they find a liaison with expertise to help guide the research project, and make connections within the community.

- An important issue to take note of in collaborative research is the reward structure, as all participants should benefit from the research, not the researcher alone.

- It is important to determine with collaborators the types of information/findings that will be shared publicly, as some findings may be deemed harmful to the organization.

Cargo, M., & Mercer, S. L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 325–50. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824

- Participatory research is enhanced as community members have the contextual expertise.

- Participatory research acknowledges that contexts vary, therefore programs and interventions cannot be considered a one size fits all.

- Often participants within research are dissatisfied or unwilling to participate in research because they feel as though the researchers swoop in, collect their data, then leave, without providing results, resources or action within the community.

- “PR is broadly defined as ‘systematic inquiry, with the collaboration of those affected by the issue being studied, for purposes of education and taking action or effecting change’ (Green, George, Daniel et al., 1995).

- PR’s strength is in the collaboration between the participants real world experience and the academics theoretical and methodological expertise.

- Participatory research is an approach therefore allows for flexibility of methods that will best suit the needs of the research project. Additionally, it creates an ideal situation for knowledge mobilization and translation, as information will be shared throughout with collaborators and require feedback throughout the research project.

- Questions to address with participatory research:

- What are the values or drivers behind the research?

- Who should participate in the research, and how should they participate?

- How are partnerships initiated, and how do they evolve?

- What are the core elements of PR?

- What is the added value of PR in each of the research phases? (p. 328)

- People to include in the research

- clients, consumers, or other ultimate beneficiaries of the PR effort—the group in which change can be measured (end users);

- the interpersonal support network of the end users—including family members, mentors, friends, etc.;

- the general public, who are not end users but support or believe in the issue;

- those who interface directly with end users and/or end users’ interpersonal networks, including practitioners, health professionals, teachers, administrators, and other pertinent staff (service providers);

- individuals who operate at an administrative or political level and typically interface with service providers and staff rather than with end users or end users’ interpersonal networks—including policy makers, executive directors, financial officers, and program administrators (administrators). (pp. 331–332)

Reflections

While the premise of a collaborative community-based project is something I would love to do, I do not think it would be feasible in terms of the timeline for a dissertation. The project would need to be sustainable and have—ideally—pre-existing relationships between the researcher and community. Although, I have recruited a liaison to work with my ideal community/school context, I don’t think the level of collaboration outlined by the above authors would be feasible. Therefore, I hope to stick to a participatory approach, whereby I will meet with stakeholders initially to discuss my proposed direction for the research and make adjustments based on their feedback. Throughout the research process, I will encourage participants to engage with the analyses through a public website (more to come on the open research approach). This in turn will hopefully lead to an opportunity for organizational learning as they engage online and reflect on their practices and thinking. Ultimately, I will conduct a small survey at the end of the research to determine the impact of this online participatory approach, as the participants may or may not have found it useful.

In terms of who would be participating within the research, I have identified two main stakeholder groups: Administrators and School Staff (See figure 1). These stakeholders all play a role within bullying prevention program implementation, strictly within the school context. Parents and students will not be directly approached (although may choose to engage online), as we seek to explore the organizational structure of bullying prevention within the school, and with those that researchers or external program implementers have directly worked with in the past. Librarians are often overlooked within the research on bullying. However, I argue that many bullying prevention programs (e.g., WITS) use books as a key part of the program.

In response to Cargo and Mercer (2008):

- What are the values or drivers behind the research?

- Understanding how bullying prevention works within the school system; understanding what happens long after the external program implementers have left; finding leverage points in which to enact change and organizational learning.

- Who should participate in the research, and how should they participate?

-

- All participants outlined in figure 1 will be invited to engage online throughout the research, as well as participate in group (admin/school staff) focus groups. Once focus groups have been completed, those wishing to participate in the interview sessions will be contacted.

- How are partnerships initiated, and how do they evolve?

-

- Contact will be made through the school board, as for the evolution, this I will need to spend some more thinking on.

- What are the core elements of PR?

- Again, I will have to navigate this more as I work through my methodology (case study; qualitative or mixed methods) and theoretical framework (social/organizational systems theory).

- What is the added value of PR in each of the research phases? (p. 328)

- Same as above.

Things to explore further

- All works refer to Israel and collaborators, so I will need to dig a little deeper into her work.

- Wallerstein & Duran, 2003 to explore their goals of community-based participatory research (research, action, and education).

- Green LW, George A, Daniel M, Frankish J, Herbert CJ, et al. 1995. Participatory Research in Health Promotion. Ottawa: R. Soc. Can. For checklist

0 Comments